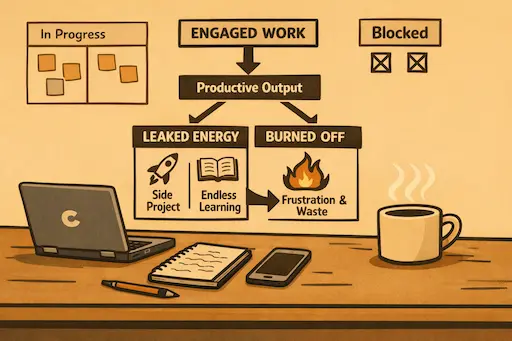

Energy doesn’t disappear. It either gets used, leaks elsewhere, or burns off fighting friction.

I’ve noticed that good developers tend to have a fairly predictable amount of energy available each day. I’m talking about cognitive energy, the kind that wants to be pointed at something interesting and allowed to do its thing. It doesn’t appear or disappear at random and if it isn’t being used, it gets converted into something else.

When that energy is properly absorbed by your day job, it tends to dissipate cleanly. You spend it thinking, building, solving problems, and by the end of the day there isn’t much left. You’re tired but in a satisfying way.

When it isn’t absorbed, it doesn’t simply vanish. It shows up as side projects. As learning for the sake of learning. As tinkering. As that low-level restlessness that pushes you to keep poking at things long after you’ve closed your laptop. The energy has to go somewhere. I’ve seen this play out in my own career often enough and maybe you have too. When I’m genuinely engaged at work. When the problems are real, the trust is there, and I’m operating in my strengths the extra outlets quiet down. Side projects disappear. Learning becomes part of the work itself. There’s no surplus. When that surplus appears, it’s usually a sign that I’m underutilised. Capable of more than I’m being asked to do.

There’s another state that looks similar from the outside but feels completely different. That’s when the work is draining rather than engaging. When energy is spent navigating approval chains, justifying decisions, or producing artefacts that exist mainly to prove that work happened. In those situations, the energy doesn’t get redirected, it gets burned off as heat. The side projects don’t appear. The learning doesn’t spike. I just end up tired.

Those two states are not the same.

Sometimes the surplus energy is almost pleasant. You finish work with plenty left in the tank. Your brain keeps wandering. You start a side project. You read a book you didn’t strictly need to read. You learn something just because it caught your attention. There’s no sense of urgency to it — just motion looking for somewhere useful to go.

Other times, the energy doesn’t leak at all. It just gets consumed. The day is full, but not in a satisfying way. Time is spent seeking approval, navigating process, filling in artefacts that exist mainly to demonstrate that work happened rather than to enable it. Even when the technical problems themselves are interesting, the surrounding friction drains something out of them. By the end of the day there’s nothing left to redirect. No appetite for side projects. No curiosity left for learning. Just tiredness.

In the first case, the system is underloaded. Energy has nowhere meaningful to go, so it spills into other channels. In the second, the system is overloaded with resistance. Energy is still being expended, but it’s being burned off fighting the environment rather than doing the work.

I’ve learned to pay attention to which one I’m in by watching where the energy ends up. If I’m starting side projects, binge-learning, or generally feeling like my brain wants more, that’s usually a sign I’m not being fully used. I’m capable of more than the role currently demands. The work isn’t stretching me, even if it’s comfortable or technically fine.

If, on the other hand, I’m napping in the middle of the day just to make it through or finishing work completely spent without feeling satisfied, that’s a different signal. That’s not excess energy looking for an outlet. That’s energy being lost to friction.

Once you start seeing the difference, it’s hard to unsee it.

This is where a simple rule of thumb I’ve carried for years starts to make more sense to me than it did when I first adopted it. A job, at any given point, should be doing at least one of three things: it should be earning, learning, or quietly preparing you for leaving. Ideally, you get the first two at the same time. Sometimes you accept one in exchange for the other. But if you’re getting neither, if you’re not well compensated and not growing, then staying put starts to cost more than it returns.

What I’ve realised is that this “energy lens” is a useful way of diagnosing which state you’re actually in.

If you’re earning well but still have a surplus of energy sloshing around, that might be fine for a while. Comfort has value. But if that surplus keeps turning into side projects and late-night learning sessions, it’s probably telling you that the role isn’t stretching you anymore. You’re being paid, but you’re not being used.

If you’re learning a lot, the energy tends to disappear into the work itself. Curiosity gets fed where it arises. There’s less leakage because the system is doing what it’s meant to do. You go home tired, but it’s the good kind of tired.

If, instead, you’re neither earning particularly well nor learning much, then the signal is different. That’s not a phase to push through indefinitely. That’s the point where leaving starts being sensible.

Energy is a finite thing, and where it ends up is usually a more honest indicator of what’s going on than how busy your calendar looks. For a long time, I think I misread those signals. I’d treat side projects as distractions instead of symptoms. I’d treat exhaustion as a personal failing instead of a systems problem. Looking back, the pattern was there. I just didn’t have a good way to describe it.

When I feel restless, curious, and full of ideas, I try not to squash it. It’s not inherently a bad thing! But I ask whether the work in front of me is actually worthy of the energy I have available. When I feel drained without satisfaction, I stop assuming I need a holiday and start questioning the shape of the work itself.

Neither state means something is wrong with you. They just mean something different is happening to your energy. There is also a valid time and place for comfort, or side projects, or increased self-learning. But once you start paying attention to this pattern, it becomes much harder to stay stuck by accident.